On 26 June 1955 the Freedom Charter was adopted by the Congress of the People (COP) at Kliptown, near Johannesburg, South Africa.

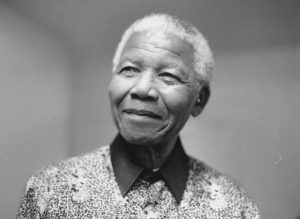

Some 3000 delegates from across the country attended the Congress over two days which was extremely difficult to organise due to the conditions of apartheid. Many of those, including Nelson Mandela, who would have attended as delegates, were banned.

The Congress presented the special award of Isitwalandwe to Chief Albert Luthuli, Dr Yusuf Dadoo and Father Trevor Huddleston. Only Father Huddleston was present to hear the cheers as Chief Luthuli and Dr Dadoo were banned.

The delegates present “included wizened black countrymen and office workers with bright American ties, smooth Indian lawyers with their wives in saris, and swaying black grandmothers in wide skirts in the ANC colours.” (Anthony Sampson, The Treason Cage, 1958)

The Freedom Charter opens with the words:

“We, the people of South Africa, declare for all our country and the world to know:

That South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white, and that no government can justly claim authority unless it is based on the will of the people.”

The Freedom Charter then lays out the requirements for a free and democratic South Africa with the aims:

- The people shall govern!

- All national groups shall have equal rights!

- The people shall share in the country’s wealth!

- The land shall be shared among those who work it!

- All shall be equal before the law!

- All shall enjoy equal human rights!

- There shall be work and security!

- The doors of learning and of culture shall be opened!

- There shall be house, security and comfort!

- There shall be peace and friendship!”

The Freedom Charter concluded, “These freedoms we will fight for, side by side, throughout our lives, until we have won our liberty.”

Background

In 1953, Professor ZK Matthews had made a call for a Congress of the People at the ANC Cape Provincial Conference. This was agreed at the following ANC National Conference and Walter Sisulu, acting on this resolution, wrote to the national executive committees of every organisation including the African National Congress, the South African Indian Congress, the South African Coloured Peoples Organisation, the Congress of Democrats (white progressives) and the South African Congress of Trade Unions inviting them to a joint conference to discuss the idea of a Congress of the People.

The conference of delegates from the above organisations agreed to attend and it was held near Stanger, Natal, to which district Chief Albert Luthuli, ANC President, had been confined by a banning order.

The conference agreed to set up a National Action Council whose composition was significant in that it served as the first truly non-racial forum for the planning of joint political work for the Congresses.

The National Action Council published a “Call”, written by Rusty (Lionel) Bernstein, which crystallised its essence as ‘Let Us Speak of Freedom’, asking people everywhere to collaborate in setting the terms of the Freedom Charter. This provided the agenda for the different organisations to set up thousands of meetings up and down the country.

“Literally tens of thousands of scraps of paper came flooding in: a mixture of smooth writing-pad paper, torn pages from ink-blotched school exercise books, bits of cardboard, asymmetrical portions of brown and white paper, and even the unprinted margins of bits of newspaper” (Joe Slovo, The Unfinished Autobiography, 1995).

A small team separated and collated all these bits of paper and then divided them into various categories of demands. From this, Rusty Bernstein drafted the Freedom Charter which was a statement of core principles characterised by the opening demand “The People Shall Govern”. The Freedom Charter was then agreed by the National Action Council and presented to the people over the two-day Congress of the People.

Congress of the People

On the first day of the Congress of the People the Freedom Charter was recited in three languages, English, Sesotho and Xhosa, and was approved with shouts of ‘Afrika’ from the crowd.

On the second day as the Congress moved through the aims of the Freedom Charter the afternoon proceedings were suddenly disrupted by plain-clothes detectives and police armed with sten guns. Another group of police armed with rifles formed a cordon. An officer took the microphone and announced that they were investigating high treason and were searching for subversive documents. The people responded by singing loudly Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika and adopting the Freedom Charter. The police took the names of all those present one by one before they were permitted to leave.

Mandela, along with Walter Sisulu, who was also banned from attending, had watched the gathering from beyond the crowd. He commented, “I knew that this raid signalled a harsh new turn on the part of the government.” He also wrote, “Though the Congress had been broken up, the charter itself became a great beacon for the liberation struggle.” (Nelson Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom, 1994)

Mandela was correct on both counts. On 5 December 1956 the apartheid police arrested 156 people from all over the country and charged them with high treason. The key document in support of the charge was the Freedom Charter. The “Treason Trial” lasted four years when eventually the last group of accused were acquitted.

The trial was partly designed to remove the leaders of the liberation movement from active struggle. However, because it brought together the leaders from across the racial divide and from across the country it welded them together and served as the organising and unifying centre of the people. It was an unintended consequence of the actions of the apartheid state.

The Freedom Charter captured the hopes and dreams of the people, and it became a great beacon for the liberation struggle throughout the ensuing decades until the end of apartheid on 27 April 1994.

The Constitution of a free South Africa is largely based on the Freedom Charter.

Brian Filling